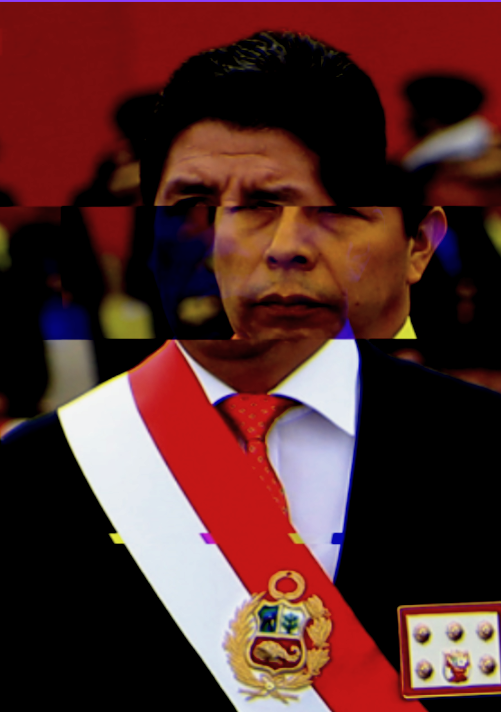

Adapted from Galería del Ministerio de Defensa del Perú – PRESIDENTE DE LA REPUBLICA Y MINISTRO DE DEFENSA PRESIDIERON CEREMONIA POR EL DIA DE LAS FUERZAS ARMADAS, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=123574400

The president of Peru, Pedro Castillo, attempted to dissolve Congress and grant himself new constitutional powers in a self-coup, but failed after Congress swiftly impeached and removed him from office. He was arrested and his First Vice President, Dina Boluarte, quickly became Peru’s first female president.

Following Mr. Castillo’s ousting and arrest, protests have rocked the country with many criticizing what they consider the kidnapping of the legal president and the draconian measures of Ms. Boluarte to put down the protests and restore order during this political crisis.

Ms. Boluarte has declared a 30-day state of emergency across the country with individual rights of citizens such as speech and assembly being restricted in her effort to assert herself as the competent, legitimate president of Peru. Over 20 people have died in these protests, and that number will likely continue to rise. But there is a clear historical precedent for Mr. Castillo’s self-coup and the violence that has followed: the 1992 successful self-coup by Alberto Fujimori.

Mr. Fujimori sought to centralize political power under him and his right-wing government and implement the Plan Verde, a plan that would revolutionize the Peruvian society and economy. Mr. Fujimori had the backing of the military, and he used this support to push for neoliberalism and fight off the terrorist Marxist group, Shining Path. He then built a brutal dictatorship to create the Peru that he desired.

While Mr. Fujimori succeeded in cementing himself at the head of Peruvian government, Mr. Castillo failed. But the potential for further devolution into political chaos is still serious. Ms. Boluarte could use the silencing of dissent with her declaration of a state of emergency to centralize power under her. Pro-Castillo protestors could become increasingly aggressive in their support to free Mr. Castillo from prison. Right-wing populists like Mr. Fujimori’s daughter, Keiko Fujimori, could capitalize on the uncertainty of this political moment to regain power in a country that has shifted to the left after Mr. Fujimori was impeached and removed while exiled in Japan.

Peru has already traveled down a path filled with political violence. Ms. Boluarte has noted that “[w]e have already gone through that experience in the 1980s and ’90s, and we do not want to return to that painful story that has marked the lives of thousands of Peruvians.” Yet the political future of Peru remains unclear. If Peru’s past is any sign of its future, there is serious potential for growing violence and the degradation of civil liberties as politicians seek to regain control of a turbulent Peru.

Alberto Fujimori

Alberto Fujimori was elected in the 1990 presidential election as a right-wing dark horse candidate, utilizing the hyperinflation under outgoing president Alan García and uncertain economic plans of the expected winner, Mario Vargas Llosa, to secure the victory. Mr. Fujimori became president while riding a wave of populism and touting neoliberal ideals. Peru was following the recommendations put forth by the Washington Consensus, a plan developed in Washington, D.C. in the United States’ efforts to oust left-wing governments and staunch Soviet influence in Latin America.

Mr. Fujimori pushed the Peruvian economy to neoliberalism with his Fujishock plan. He reduced subsidies and tariffs, removed price controls, and artificially boosted the economy by quadrupling the minimum wage and establishing a $400 million poverty relief fund. His reforms created economic uncertainty that hurt the impoverished people he claimed he was helping.

Mr. Fujimori is a controversial figure in Peruvian history because while he was generally able to turn Peru’s economy around from the hyperinflation of his predecessor to a period of economic growth, he quickly became a despot, consolidating power in the executive branch to execute the clandestine military operation known as Plan Verde.

Plan Verde

Originally planned to be implemented after the potential overthrow of Mr. García in 1989, Plan Verde outlined a hard right turn for Peruvian society and economics. Reeling from the country’s financial woes, the Peruvian Armed Forces planned to oust Mr. García from power and seize control of the government. This plan was pushed back until Mr. Vargas Llosa’s anticipated victory in the 1990 presidential election; after Mr. Fujimori pulled off a surprise win at the polls, Plan Verde became incorporated with Mr. Fujimori’s other political goals and became a driving force in his government from the shadows.

Plan Verde had four main goals: turn Peru into a neoliberal nation, repair ties with the United States by cracking down on drug trafficking, establish a propaganda regime with harsh censorship against critics of the Fujimori government, and prevent the resurgence of poverty in Peru by forcibly sterilizing any impoverished or Indigenous people.

Prior to Mr. Fujimori’s election in 1990, Plan Verde had no real influence over the direction of the government given that Mr. García, as a socialist, would clearly resist a push toward neoliberalism. A coup was therefore planned but never came to fruition because Mr. Fujimori provided Plan Verde the opportunity to effect change in Peru in a legal manner. He was able to govern according to his will for some time before deciding that his goals transcended the legal framework of Peruvian politics. So in 1992, he successfully staged a self-coup to remain in power as a dictator.

Dictatorship

On April 5, 1992, Mr. Fujimori announced that he was dissolving Congress and the judiciary, allowing himself to assume full legislative and judicial powers. Without the other branches of government to keep him in check, Mr. Fujimori was free to implement whatever policies he desired, including Plan Verde. But a critical component to Mr. Fujimori’s success in staging this self-coup was the fact that he had the backing of the military. Military support allowed Mr. Fujimori to take complete control of the government without fear of being ousted himself, be it by impeachment or a rival coup.

The rapid expansion of Mr. Fujimori’s power allowed him to execute the reforms of Plan Verde. Over the rest of his administration, which spanned from 1990 to 2000, the government forcibly sterilized approximately 300,000 Peruvians. This sterilization campaign served the dual purpose of creating Mr. Fujimori’s ideal Peruvian makeup through eugenics while garnering international support for his government, notably from that of the United States. Paired with Mr. Fujimori’s plans to crack down on drug trafficking, the U.S. supported Mr. Fujimori’s sterilization efforts, a crime for which Mr. Fujimori is under legal scrutiny.

Mr. Fujimori is currently serving a 25-year sentence for crimes against humanity for his role in supporting the Grupo Colina death squad, which hunted down and killed people associated with the Shining Path, most notably in the Barrios Altos massacre, the Santa massacre, the Pativilca massacre, and the La Cantuta massacre.

Brought to power under the guise of economic altruism, Alberto Fujimori quickly became a murderous dictator willing to do anything to gain more power. His 1992 self-coup started a country-wide tailspin, and the attempted self-coup of former President Pedro Castillo has the potential to push Peru into a repeat of this chaos.

Pedro Castillo

Pedro Castillo’s tenure as president was controversial from the start. On a left-wing populist platform, Mr. Castillo vowed to overhaul the political system to address rampant poverty. His rival in the 2021 presidential election was Mr. Fujimori’s daughter, Keiko Fujimori. The final tally was close enough for Mr. Castillo to secure the win, but Ms. Fujimori was quick to claim election fraud. There is no proof for such claims, but Ms. Fujimori introduced uncertainty in Mr. Castillo’s administration.

Because of the contentious election, Ms. Fujimori set up an enduring political battle against Mr. Castillo. She spearheaded efforts to impeach and remove him for corruption, liberally using the Constitution’s language that a president can be removed if they are deemed to be “morally unfit.” Two impeachment efforts failed to remove Mr. Castillo from power, but these attempts were not the only controversies marring his presidency.

Mr. Castillo’s cabinet experienced over 50 personnel changes in the first year, and his approval among the people he sought to represent plummeted because of Mr. Castillo’s inability to make good on his campaign promises. Mr. Castillo was losing control of his government due to myriad internal conflicts, and with a third impeachment looming, he decided to follow Mr. Fujimori’s example and stage a self-coup to grow his power.

Self-coup and ousting

On the morning of December 7, Pedro Castillo broadcast a message in which he declared that he was dissolving Congress, forming a provisional government, instituting a national curfew, and calling for a new constitution. The fallout from this declaration was swift and widespread: Prime Minister Betssy Chávez, Minister of Labor Alejandro Salas, Minister of Economy and Finance Kurt Burneo, Minister of Foreign Relations César Landa, and Minister of Justice Félix Chero resigned in protest Mr. Castillo’s self-coup.

Unlike Mr. Fujimori, Mr. Castillo lacked the support of the Constitutional Court and the Peruvian Armed Forces. Mr. Castillo was alone in his attempt to stay in power, and the other keys of power in Peru refused to support his effort to stay in power. Congress voted to impeach and remove Mr. Castillo, with 101 votes in favor, 6 against, and 10 abstentions. Mr. Castillo attempted to flee to the sympathetic Mexican embassy but failed to secure asylum.

Mr. Castillo was arrested for rebellion and conspiracy and is being held in the same prison as Mr. Fujimori. Mr. Castillo’s First Vice President, Dina Boluarte, was sworn in as president, and she is now leading Peru through nationwide protests with force.

Protests

The cities of Lima, Ayacucho, Cusco, Ica, Arequipa, Trujillo, Chiclayo, Huancavelica, Huancayo, Tacna, Jaén, Moquegua, Ilo, Puno, Chota, and Andahuaylas are embroiled in protest. Ms. Boluarte has proposed holding elections earlier than the next scheduled ones in 2026, offering 2023 or 2024 as the potential years, but Congress has rejected this plan as unconstitutional.

Ms. Boluarte’s clearest and most aggressive response to the protests after Mr. Castillo’s arrest is her declaration of a state of emergency, which suspends some of the constitutional rights of citizens, including the freedom of assembly, a clear attempt to make these protests illegal. Peruvian security forces have responded to protests with force, killing 23 people as of December 18. Hundreds more have been injured.

Peru is in crisis, with some leaders recognizing Ms. Boluarte as president, while others still recognize the ousted Mr. Castillo as the legitimate leader of Peru. After Mr. Castillo’s failed coup to empower the executive branch, Ms. Boluarte has used the chaos of this moment to clamp down on dissent and legally take power from the people.

Mr. Fujimori capitalized on the rise of the right wing by staging a successful self-coup to become a dictator and impose his despotic will on Peru. Mr. Castillo illegally tried to stay in power in the face of a third impeachment attempt, but failed to see the same success as Mr. Fujimori. Now, Ms. Boluarte is trying to wrest control of the country from the protestors by injecting more power into the executive branch.

Peru has already traveled down a path of political turmoil, starting with a 1914 coup and repeating eight more times up until today. Peruvian politics have proven to be highly turbulent throughout its history. Ms. Boluarte must rise to be the leader that stabilizes her country, but if her first executive decisions are portents of what is to come, Peru will surely face a tumultuous road ahead.